ASTRO-ATLANTIC HYPNOTICA FROM THE CAPE VERDE ISLANDS

This is the story of how immigration from the Cape Verde Islands to Europe, propelled by despondence and upheaval at home, gave us an alternate history of electronic music, which captured the hearts and minds of partygoers and audiophiles across the world, giving rise to a new global music It’s why Portugal’s napalming of Mozambique, and deployment of over 30,000 troops in Guinea-Bissau, when the U.S. was winding down its wars in Southeast Asia in the early 1970s, remain an under-reported footnote rather than a concrete memory.

In 1980, a young aspiring footballer, Narciso “Tchiss” Lopes, emigrated from the Cape Verde Islands to Portugal. A member of the world’s largest diaspora per capita Cape Verde has more people living outside its borders than within it – Lopes left his home island of São Vicente, migrating first to Lisbon, where Cape Verdean immigrants are well represented in Portugal’s football leagues. A few years later, as a sailor, Lopes moved to the Italian capital to pursue a career in music.

“In the beginning it was very difficult,” Lopes said. “In Italy, it wasn’t the most welcoming environment – even if we wanted to learn new skills, the doors were closed.”

The pain of seeing his compatriots unable to get jobs and “sleeping on the streets” inspired his definitive LP, “Stranger Ja Catem Traboi,” a roaring, high-tempo, synthesizer-filled take on Funaná rhythms which speaks to the hardships of the migrant experience. Listen close enough, and the patterns and arrangements don’t differ greatly from what we know today as “electronic” music.

Rome has the fourth largest Cape Verdean community in the world, after Portugal, the United States and the Netherlands. And despite initial travails, the 1980s, Lopes said, “Were very special, not just for me but for a lot of people.” Migration hadn’t reached the haunting crisis one sees today, hardening attitudes and given right-wing politicians a pulpit. For Lopes, as a musician, the climate “took more care of the artists,” allowing for a laboratory of sorts to form within the community.

“In Cape Verde, we had no access to electric instruments,” he said. “In Europe, we had access, but we had to adapt. Audiences expected electronic sounds, but we still stayed true to our sound.”

“At first,” Lopes continued, “the music was just to cater to Cape Verdean immigrants, but soon, people of Napoli especially started feeling it, then Rome.”

That feeling would transpire across Lisbon, Paris, and Rotterdam, as one the largest waves of migration from a single country sent thousands of Cape Verdeans to Europe’s cities. Most who made the uncertain journey took up maritime jobs as sailors and dockworkers by day, musicians by night.

Movement and mobility are intrinsic aspirations of the human condition. What we’ve come to know as immigration is as old as civilization. Yet today we measure immigration through a series of vapid data -how many refugees have entered? How many jobs have immigrants created? What percent of Europe are naturalized citizens? – and either condemn the nefariousness of the potentially incompatible outsider or celebrate the brilliance and success of the most scientific and business minds. Immigrants are either threats or treasures, rarely occupying a space in between. As Lebanese satirist Karl Sharro joked in a tweet: “As an immigrant myself, I’m not comfortable with society measuring the worth of immigrants by their ability to invent the iPhone.”

Very rarely do we peer back into the past to examine the tangible and timeless creations born from the largest movements of peoples, overlooking cultural innovations arguably ahead of their time, precursors to consuming global trends.

Economy led by New York, Chicago, and London in the late 1990s. But the story doesn’t start in a Western cultural hub, rather in the small cluster of islands 400 miles off the Senegalese coast, and offers an unparalleled insight into the long-term cultural splendor catalyzed by migration.

Cape Verde today is justifiably hailed as an African political success story ranked third out of 54 countries on the 2016 Ibrahim Index of African Governance – but things were different in the 1980s.

A war of independence won autonomy from Portugal in 1975, making Cape Verde and all of Portugal’s colonial holdings in Africa some of the last countries to achieve decolonization. The nine island chain suffered the familiar ails of a society born from colonialism and slavery struggling to integrate politically and economically into a globalized Anglophone world moving faster than can be caught by a Lusophone people isolated by Lisbon’s colonial design. To quote Frantz Fanon’s assessment of colonized societies, Cape Verde was “starved of bread, of meat, of shoes, of coal, of light.”

Under the military dictatorship of General António de Oliveira Salazar, it remained a key policy to shroud Lisbon’s colonial exploits and the extent of violence in Cape Verde, Guinea Bissau, Angola, São Tome, and Mozambique from the outside world, creating an alternative Lusophone realm virtually impregnable to Anglophone interest, coverage, or empathy. As a result, Portuguese- speaking African Countries, designated as PALOP, their stories, myths, and culture, largely evaded the global reach and cultural clout of Anglophone mass media. Only a handful of scholars in Anglo-American academia have focused their efforts on Lusophone Africa. This detachment from a rapidly advancing world fostered a yearning to integrate, to connect in anyway possible. The new found homes in the multiculti metropoles of Europe offered little respite. In Portugal, for instance, “The mass media as producers of identity,” writes Luis Batalha in Transnational Archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean Migration and Diaspora, “have created a negative image of Cape Verdean immigrants, especially their descendants.”

“While the first migrants were depicted as good workers – although “hot blooded” – their descendants are seen as dropouts and juvenile delinquents.”

Batalha reveals that Cape Verdean identity has no designation in Portuguese social designs. “Their identity has not been hyphenated,” he writes, “the category of ‘black Portuguese’ does not exist as such.”

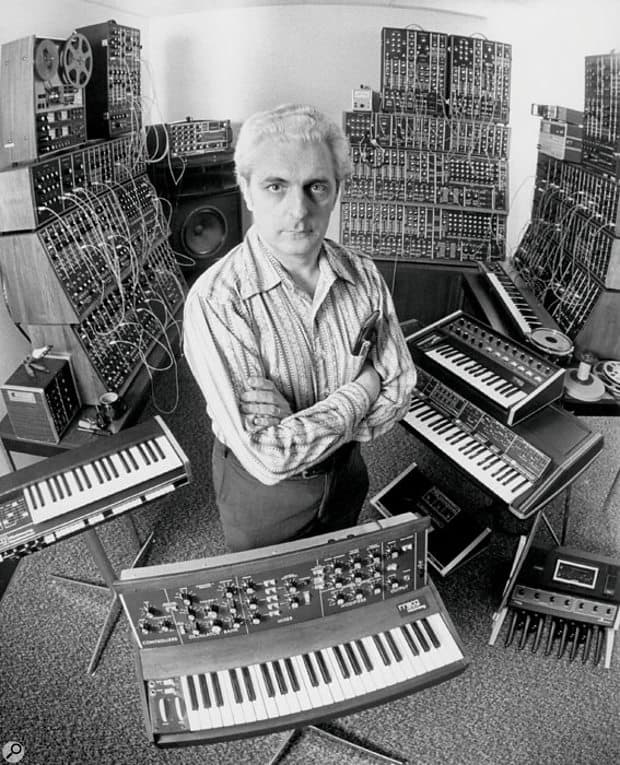

Consequently, the ready availability of electronic instruments, a doorway to a long denied ‘modernity’ and an anchor in their adopted homes, was seductive.

“Cape Verdeans were celebrating their independence and with that the dancing became even more important,” said Val Xalino, an unsung hero in the development of his country’s electronic sound, based in Gothenburg, Sweden. “People wanted to hear something different. They wanted the synthesizer!” “People told me that I was a revolutionary,” Xalino reminisced, “but I didn’t understand that back then.”

“Every place we play, the Cape Verdean community, we worked hard to create dance halls for them, and they loved it because that kind of music was new to them,” said Jovino Dos Santos, a widely respected elder statesmen of Cape Verdean music, who also started in Portugal, before settling in a suburb of Paris, France.

This compilation is defined by the music of Santiago, home of the capital, and its native rhythms of Funaná and Batuku, the last to be utilized in popular music. Each island, because of ocean currents and colonial restrictions on travel developed its own fiercely independent culture. The older generations may still identify with an island rather than the nation. Santiago remains most closely But there are two reasons for this,” Gomes continued, “first is Paulino, the other is that the 1980s was an era of tremendous access and innovation of new technologies, new instruments, new tools.”

Live performance spaces and discotheques like Monte Cara, now known as Enclave, and Lontra, became attached to its mainland African heritage, the savored epicenter of the Lusophone “They use to listen to slower Mornas and Coladeiras from Cape Verde,” he continued, “and then we give them something new, something they couldn’t have before.”

The Cape Verdean diaspora is well coalesced and connected to the homeland. Musicians have regularly returned to the islands for extended periods of time, and continue to do so today. When Rotterdam-based seminal band, Bulimundo, travelled back to Cape Verde, their luggage contained stock of synthesizers and MIDI instruments. Travel to the countryside to learn the rhythms of rural farmers became common. The melodies of the charmingly off-tune, often damaged accordions were transplanted onto synthesizers.

A cultural supply chain was established. Largely detached from global capitalism, music was, and in many ways still is, perhaps Cape Verde’s most effective gateway to integrating with the world; immigration its engine and lifeblood.

As the gadgetry of the day penetrated the islands, the hearts and minds of a musically-inclined people, particularly the youth, were captured. One mercurial youngster, Paulino Vieira, arguably Cape Verde’s most important musician, the real mastermind behind the islands’ melodic majesty, was especially drawn to keyboard instruments, having honed his skills at a Catholic seminary run by Padre Simeoes, widely credited as a defining influence for several musicians.

He not only arranged, composed, or played on at least half the songs on this compilation, but was the invisible hand behind the compositions of Cesaria’s Evora’s first album, Sodade, which launched her to worldwide fame, deepened the pockets of producer Djo da Silva, and registered Cape Verde as a cultural force in the global imagination.

Evora was from the island of Fogo, in the southern belt of Sotavento islands. Her heartfelt, cavaquinho and violin-driven delicate songs fueled by ‘saudade’, a sense of longing, became the signature sound readily associated with Cape Verde. typified by its refining of Funaná and Batuku, with their origins in what’s today Guinea-Bissau.

Praia was the seat of the Portuguese colonial elite, the city center once home only to whites. After independence, left- winged nationalist party, PAICV, purged Europe’s colonial infrastructure. Praia was transformed into a city prideful of its African ancestry. Opportunity attracted aspiration. As more people of varying socioeconomic and racial strata mixed in the capital, the structures of a once imposed isolation between the islands slowly withered, Africanizing a diverse country in a way that environment and colonial dictates made impossible.

It was this, the most African of musics, of the rural poor, affectionately yet disparagingly known as the badius (vagabonds), developed in a junction

of the Atlantic, that traveled to Europe to be reinterpreted, ushering in a little known proto-electronic movement, which predated the curiously all-too-familiar sound in Chicago, New York, and London by over a decade, often complete with a repetitive 4/4 beat.

The movement found its headquarters in Lisbon, where Paulino Vieira had immigrated at age 18 to lead a reworked Voz de Cabo Verde, the commanding, enigmatic ensemble that electrified Santiago’s folklore and enticed Cape Verdean musicians from around the diaspora to collaborate.

“Paulino was the most visionary,” said Elisio Gomes, a Paris-based multi-genre singer who collaborated with Vieira on two albums — including “Chuma Lopes” — of Funaná and Batuku in the mid-1980’s. “He always had this gift to be 10 years ahead of his time. That’s why our music sounds like it was produced today.” African diaspora in Portugal’s coastal capital, centralizing an ultra-progressive sound born under Vieira’s auspices.

But, as in Italy, according to Gomes, the diaspora was joined by “lots of Europeans, from Portugal and Spain, attending the clubs,” culminating in the legendary 1987 founding of the Baile nightclub inside a ballroom of the iconic Palácio Almada de Carvalhais by prominent Portuguese lawyer José Manuel Silva.

Overlooked outside the Lusophone realm until now, Cape Verde’s Astro-Atlantic gumbo of instrumentation and rhythm offers a timely lesson of migration’s power to produce cultural innovations ahead of its time. Whether it was Jovino Dos Santos in Paris, Tchiss Lopes in Rome, Val Xalino in Gothenburg, or Paulino Vieira in Lisbon, this sound could not have been perfected without the induction of Cape Verde’s artistic human capital into the West.

As we watch with heavy hearts the tragic crisis unfolding across the Mediterranean, as people fleeing similar circumstances strive to settle in Europe, a measured hint of patience will ultimately justify their vast inclusion. There are poets, writers, artists, thinkers, and, of course, musicians, raised in an age of technology, that are making the treacherous journey by boat, or by land on foot, from Syria, Eritrea, Libya, Iraq, and elsewhere. Paulino Vieira’s heir, and lush cultural innovation bound to bare the same fruit, lie among them. and guitar pedals in their dance music styles. In a way, they were inadvertently anticipating the foundations for electronic music that dominated the music scenes of London, New York, and Chicago in the late 1990s. Why is it that these islanders were on the cutting edge of popular world musical developments? The proximity of Cape Verdean transnational diaspora communities to international culture common ground the Biguine, Cumbia, and more recently Zouk from the French Caribbean-on a regular basis. Although these styles originally featured a small ensemble of acoustic string instruments, this was gradually modernized. By the 1960s groups like the important Rotterdam-based band Voz de Cabo Verde changed the scene by using amplified instruments on a regular basis, with sets that added Off the coast of Senegal and Mauritania, the Cape Verde (Cabo Verde, Cap Vert) islands are small and remote but musicians from this Atlantic archipelago have been well integrated into the international popular music ecosystem since the island nation became independent from Portugal in 1975. Located along strategic Atlantic shipping lanes, Cape Verde is part of the Black Atlantic exchange web that has transported people, goods, and musical styles back and forth between the continents. Today’s Cape Verdeans (est. pop. 500,000) are the descendants of Portuguese settlers, African laborers, and other seafaring folks who made the islands their home. Cape Verdeans share a complex genetic heritage, a love for music and dance, and a creole language called Kriolu, rooted in Portuguese and West African sources. This language is also used in Cape Verde’s colonial neighbor Guinea- Bissau, allowing popular songs and styles to flow freely between them.

Like its people, Cape Verdean musical traditions have diverse influences as well, incorporating features from Africa, Europe, Latin American, the Caribbean, and North America into distinctive genres. This compilation highlights some of the truly innovative and experimental Kriolu sounds from the 1980s that defined dance halls throughout the Cape Verdean diaspora. Musicians borrowed freely and imaginatively from a host of styles from both sides of the Atlantic, and they wholehearted embraced new keyboard synthesizer sounds, drum machine, centers of creativity is one answer.

To put Cape Verdean music of the 1980s into context, we need to look at least as far back as the 1960s when two well-established musical styles were popular throughout the Cape Verde islands, the Morna and the Coladeira. Mornas are mid-tempo, nostalgic creolized ballads with roots in the nineteenth century, sharing roots with Portuguese Fado and Brazilian Modinho. The imagery in Morna lyrics is poetic and refined: the style is said to express the “soul” of the Cape Verdean people. The singers Cesária Évora and Bana (featured on this album) both helped to bring this national song form to the ears of the world through their recordings. Those performers also mixed their sets with Coladeiras fast dance tunes that share stylistic Latin American Cumbias, Bossa Novas, and sambas to the obligatory Mornas and Coladeiras.

From 1961-1974, Portugal’s colonial holdings in Africa (Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea- Bissau) fought Portugal in a war for their independence, and under the leadership of Amilcar Cabral, they eventually won autonomy. Cape Verde and Guinea-Bissau were closely aligned during and after the war, sharing the same government from 1975 to 1980. But the islands eventually adopted a multiparty system that has proven to support one of the most stable democratic governments in Africa. The war and subsequent indepedence had many important effects on musicians from Cape Verde. The turbulent times motivated many Cape Verdeans to move to diaspora communities in Europe (especially to Portugal, Holland, Italy, France, and Luxembourg), South America, mainland Africa, and southern New England, where there has been a Cape Verdean presence for several hundred years. In these new urban locations in Europe and the US, musicians were exposed to a wide range of new popular styles and instruments. The 1970s and 80s funk, rock, reggae, and disco scene, especially the works of black artists like James Brown, Stevie Wonder, the Jacksons, George Clinton, and Bob Marley left deep impressions, as did the sounds of MPB from Brazil. Latin American and African styles were also heard in urban centers like Lisbon, Paris, Rotterdam, New Bedford, Dakar, and Rome. Cape Verdeans living in those cities soaked

up these new sounds, and began enthusiastically experimenting in their own recordings, seeking a new sound for a new nation.

Cape Verdean musicians at home and abroad have often used music as a mean of protest and social commentary. In fact, revolutionary leader Amilcar Cabral recognized and encouraged the role of musicians in the struggle for independence and the nation building process. During the 1960s, some musicians wrote new Mornas and Coladeiras with lyrics that were critical of the colonial Portuguese regime. In the 1970s and 80s, others reworked traditional African-influenced folk styles that were repressed and even forbidden under the Portuguese regime, especially music from Santiago, Cape Verde called Funaná and Batuku. Traditional Funaná was originally played on the diatonic button accordion (gaita) and a homemade iron scraper (ferrinho). These styles have joined the Morna and Coladeira as national symbols of identity since independence in 1975.

Funaná and Batuku are associated with Afro Cape Verdeans living in the interior of Santiago, a fiercely independent population that has retained close cultural associations with Africa. Descendants of enslaved West Africans, these folks are sometimes called badius, from the Portuguese word meaning “vagabond,” as they did not easily conform to the wishes of the colonial regime or the mores of the Catholic Church. For years, authorities tried to censor Funaná and Batuku dances styles, which they considered to be lascivious and immoral. They also worried (with good reason) that dissenting ideas could be spread through badiu song lyrics. Both Funaná and Batuku singers use “deep Kriolu” Santiago dialect in their songs, and the lyrics are full of parables, metaphors, and deep meanings that are not readily understood by outsiders. Santiago musicians did in fact help to feed the revolutionary spirit during the war, and they have been a powerful force in establishing a colorblind democracy in Cape Verde since 1975.

During the 1970s, traditional Funaná styles were reworked and reborn by a young generation of Cape Verdeans who replaced the accordion sound with keyboard synthesizer and rock band instrumentation. With its close couples dance, Funaná created a mini-revolution in Cape Verdean dance halls throughout it large diaspora population spewed across the continents.

Funaná was not initially accepted by Cape Verdeans from all social classes or islands of origin. The Cape Verdean reinvention of traditional Funaná as a new popular dance style mirrors the earlier Nuevo Canción movement in South America in the sense that musicians drew on the sounds and

images of rural people to acknowledge their cultural contributions and intrinsic value in the face of colonial ideals. Before independence, European cultural contributions were highly esteemed in Cape Verde, but its African heritage and styles like Funaná were often repressed or disregarded-Funaná was simply too “black” for some folks, who continued to identify with older styles like the Morna and Coladeira.

Young musicians from the bands like Bulimundo, Kolá, and later Finaçon, sought out traditional Funaná accordion players, learned their songs, and

began playing them with new rock instrumentation. This new Funaná had a fast tempo and a hot new dance style that rapidly spread across the diaspora. Song lyrics often expressed pride in Santiago culture and adopted pan- African sentiments. However, Cape Verdean musicians in the 1970s and 80s had to travel to Europe or the US to make recordings because there were no suitable studios in the islands. Key individuals within the closely connected Cape Verdean transnational community helped their compatriots to record, arrange, and distribute their records. In Lisbon, Bana and Paulino Vieira played an especially important role in this process. The singer Bana owned a small record label and a nightclub that featured top performers on a regular basis. In 1973, Vieira was initially recruited by Bana to play in his backup band. Vieira went on to not only become a member of Bana’s “house band” but also to arrange and record over 100 LPs of African music. Vieira is one of the finest Cape Verdean musicians of his generation, and he has worked with many major recording artists including Cesária during his career.

A significant number of Cape Verdean musicians spent time in Lisbon before eventually moving on to Rotterdam, Paris, or southern New England.

Recording studios sprang up in these other locations, as well. For example, the Santiago-born musician Norberto Tavares was one of the first to update the Funaná sound in the late 1970s in Portugal: his widely imitated keyboard synthesizer sound became a key marker of the Funaná sound when he replaced the acoustic accordion sound with synthesizer and added drum machine to the mix. He established a recording studio in New Bedford, MA, where he recorded and arranged his own music, as well helping dozens of other artists release recordings of their music.

In the 1970 and 80s, Paris, Lisbon, Rotterdam, Boston, and Providence were musical melting pots for immigrants who cooked up sounds and styles. Cape Verdean musicians living in these cities quickly adopted new technologies, fueling a burst of exceptional creativity that we can hear in this album. Although they soaked up new ideas from African and other international musicians, they were most interested in new developments within their own extended community-the musicians stayed in close touch through family connections, tours and recordings. Unlike the releases of Cesária Évora, which were carefully crafted by José Silva in France for an international audience, the selections on this compilation are from LPs made in small batches marketed towards the extended Cape Verdean community.

Several songs in this compilation represent variations on the hard driving Funaná sound based in Santiago, Cape Verde in the 1980s including Elisio Gomes & Joaquim Varela with “Chuma Lopes;” Tchiss Lopes’s song, “E Bo Problema,” and Pedrinho’ song, “Chema;” Tulipa Negra’s “Corpo Limpo.”

Other tracks demonstrate how the creative spirit of the times led to experimentation and fusion with new styles and new instruments, especially keyboard synthesizers and guitar pedals. In the clubs of Europe and the US, Cape Verdeans would have seen firsthand the success of bands that incorporated new MIDI-based electronic instruments, like those in the French Caribbean zouk movement, which exploded during the same time period. For Cape Verdeans, using new technologies aligned well with the developing new post-independence spirit, which strove to find its own way in the modern world.