On Turkish Music

Islam and music

Some orientations within Islam have a restrictive view on music that is performed solely for pleasure. Music is seen as a strong way to affect people and should be used to speak the religion. Many orthodox Moslem leaders were hostile to all music. Azan, the Islamic call to prayer, did not count as music and was therefore permitted. Consequently a great deal of creative power was put into the azan, which developed an intricate musical form within the narrow limits dictated by religion and practical considerations.

As Islam spread throughout Asia Minor, it invaded areas where there already existed a host of musical traditions, some of them related to various religions. Although many Moslem leaders banned music and dancing, Islam was clearly unable to supplant the function of those activities in the lives of individual people and social groups.

Traditional forms of art music and folk music lived side by side with the new religion.

Particularly vigorous art music traditions existed within the boundaries of the ancient Persian Empire. This region brought forth many Arab theorists of music, among them the 11th-century scholar Ibn Sina, known to western civilization as Avicenna. These theorists’ devised sophisticated edifices of music theory

At popular level there developed any number of local variations of Islam, incorporating elements of the local religion. These local variants took a less hostile view of music than orthodox Islam did. The upshot was that, in spite of its opposition to music in principle, in practice Islam tolerated music and music making. Of course, music was modified under the influence of Islam. For instance, forms resembling the azan acquired a superior status to other traditional musicals forms. Then again, the Islamic view of women has made women performers a rare feature of traditional Arab music, at least on official occasions. It is only in our own age that female vocalists have become common, and their activities have been mainly confined to popular music.

Female instrumentalists are also very few in number, just as in Western countries.

Religious Societies

Even before 1000 A.A., Islam had developed a less dogmatic and more emotional stream known as Sufism. The Sufis (the name comes from the Persian suf, meaning wool, because the Sufis wore simple woollen clothing) were often influenced by Christian mystics and by Buddhism. They stressed the virtues of meditation and they developed ideas concerning different stages on the way to oneness with God. A series of such stages could comprise contrition, abstinence, self-denial, poverty, patience, trust in God, blessedness.

Various movements developed within the Sufi movement itself, and their adherents formed brotherhoods with rules of their own, just as monastic orders and orders of chivalry were formed within Christian civilization at the same time. The members of these Sufi brotherhoods came to be known as dervishes (from the Persian dervish, a beggar) or fakirs (from the Arab faquir, also meaning a beggar).

Some of these brotherhoods, particularly the Mevlevi confraternity and the Bektashi confraternity, got big significance for the music in Turkey.

Glimpses of the history of Turkish music

The Mevlevi confraternity

To many Dervishes, music and poetry were vitally important as a means of contact with God. Many of the popular religions employed music and dancing to achieve a state of ecstasy.

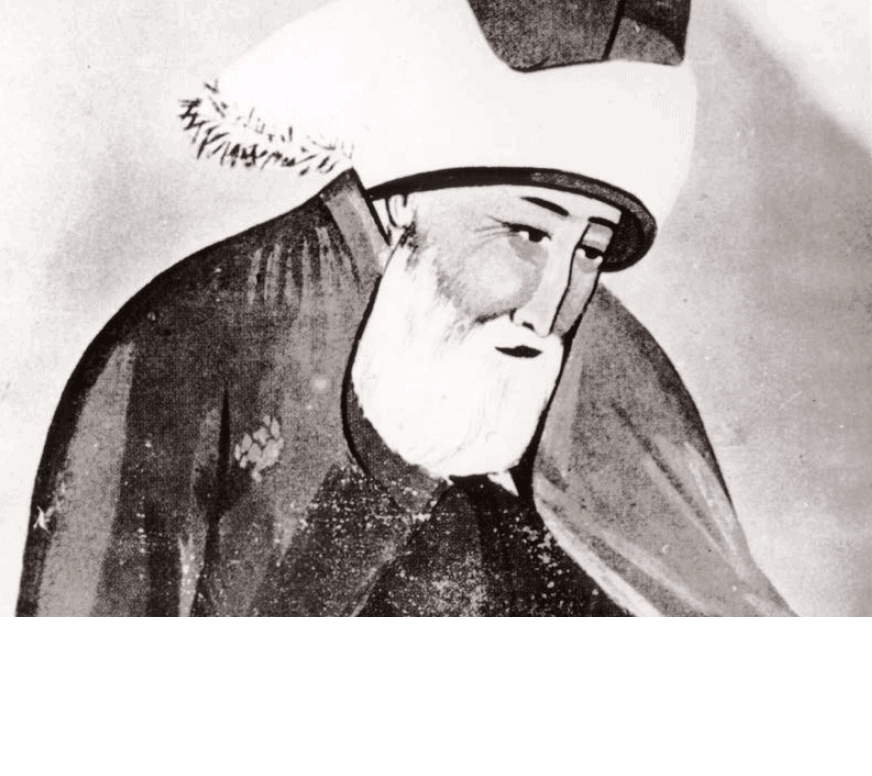

Balkh was the birthplace, in 1207 A.D., of a man best known by the name of Mevlana Jelaleddin el Rumi, our Master Jelaleddin from Rum, i. e. Turkey, or Rumi for short. Medieval poets, philosophers etc. are often known to us by more than one name, because we have their names in Persian, Arabic and Latin. Rumi was the son of a celebrated philosopher. The family fled from their home because of the upheaval caused by a Mongol invasion some time after1210. After a long caravan journey by way of Mecca, Damascus and Hamma, they settled in Konya, which at that time was the Turkish capital. Rumi remained there until his death in 1273.

Under the influence of a peripatetic Dervish mystic, Rumi began to develop an introvert philosophy of love whose most important elements were poetry, music and dancing. He expressed his thoughts in poems, which his disciples codified into three books.

dervishes” were formed.

Here is Rumi’s description of the ney flute

“Hear how the bamboo pipe

breathes

ardent love and fiercepain

after it has been pulled up from its marshy bed.Fired with the spark of love

I am drunk with the wine of love itself.

If you would know how lovers are afflicted, listen to the bamboo flute. “

After Rumi’s death, a Dervish order called the Mevlevi confraternity was founded in Konya by his son together with other disciples. This confraternity elaborated Rumi’s philosophy, and its members became known as “the dancing Dervishes” on account of the conspicuous part allotted in their rites to ecstatic dancing. This dancing was probably part of the traditions of Balkh. The type of dance performed by the Mevlevi confraternity is called sema (heaven), and one interpretation has it that the gyrating movements of the dancers represent the courses of the stars and planets.

The Mevlevi confraternity spread over a wide area, one branch of it extending as far as India. In Turkey itself, the confraternity became attached to the court of the Sultan, and it profoundly influenced Turkish art music. Very little is known concerning the ceremonies and music of the Mevlevi confraternity before the end of the 17th century, and so we do not have the least idea what their music can have sounded like in Rumi’s day. From the 18th century onwards, however, we have a more or less living tradition down to our own times.

All skilled musicians in the Mevlevi confraternity were given the title Dede (“venerable man of advanced years”), and because they were often referred to by this name and none other it is not easy to identify personalities in the history of Turkish art music. But many of the Sultans were also musicians, among them Selim III (1760–1808), whose reign marked the beginning of a period of greatness in Turkish art music which was to last until the second half of the 19th century.

The music of the Mevlevi confraternity and other Dervish orders was employed both in cult ceremonies and in other guises as a sort of refined chamber music, usually in the form of suites with pieces of different kinds succeeding one another.

The Mevlevi confraternity was banned in 1925 as part of the process of Europeanization that followed the end of the First World War. In 1954 it was once again allowed to practice dance sema because it was a major tourist attraction.

The ceremonies of the Mevlevi confraternity are led by the local head of the confraternity, who is called

- 1. Nait – solo song (prayer).

- 2. Taksim – improvised solo by ney bashi.

- 3. Peshrev – played by the full instrumental ensemble. Preparations for the dance. This part sometimes ends with a breathing exercise or

zikir - 4. Ayin – the central portion of the ceremony, comprising four

selam (greetings, prayers) sung by the vocalists to an accompaniment by the orchestra. An ecstatic dance, sema, in which the dancers whirl round in full-length white skirts. - 5. Son peshrev, yürük semai – instrumental pieces. The dance continues.

- 6. Son taksim – improvised solo on the ney or tanbur. End of the dance.

The entire ceremony closes with a unison expiration; “Huuuuuuuu” and is thus based on the sequence introduction – rising tension – relaxation.

The Mevlevi confraternity is not the only one whose ceremonies are accompanied by music. Other Dervish orders e.g. the

The Janissaries

The Janissaries, founded at about the same time as the Mevlevi confraternity, were not Dervishes but an order of warriors, rather similar to the crusading orders of European knight-hood. Many of the janissaries belonged to the bektashi confraternity. They soon became the nucleus of a victorious Turkish army, and they were widely feared, not least in Eastern Europe, where the “cruel dog Turk” displayed a ruthless ferocity.

The Janissaries employed music to put valour into their own ranks and fear into the hearts of their enemy. In the 13th century this music was played on the zurna (a sort of oboe), and the davul (a big drum), a combination which is still common in Turkish folk music [# 6]. The Janissary band – metherhane – grew up round this nucleus with the addition of trumpet-like instruments, kettle drums, cymbals etc. the music they played was loud music intended to carry a long way in the open air, unlike the contemplatic and ecstatic music of the Dervishes. In time of war the metherhane played every day outside the Sultan’s tent, while in time of peace it played at the court in Constantinople.

The music played by the victorious Turkish army must have struck the Europeans as being highly useful music invested with a great deal of magic power. The Europeans imitated the instruments and musical style of the Turks, and thus the foundations were laid of what developed into European military music. In the early 18th century, the king of Poland received a mehterhane as a gift from the Turkish Sultan (the musicians were serfs). It quickly became a fashion with Turkish chapel at the European court.

If one could not find Turkish musicians, Africans were enlisted instead. Trumpets and percussion instruments made their appearance in opera, and the influence of Janissary music can be seen in works like Mozart’s The Abduction from the Seraglio and Haydn’s Military Symphony. The whole of the military band as we know it in Europe has evolved from the mehterhane.

The order of Janissaries was dissolved and banned in Turkey in 1826 because it had become too much a power in its own right and the Sultan felt that his position was threatened. For all the influence it has exerted, we do not know today exactly what the music of the Janissaries sounded like, but the Military music will perharps convey some impression of it.

Folk music

Turkish music resembles the folk music of other countries in that we know very little about its history. Obviously the infantry of the Turkish army and the people of the villages both sang and played. In countries such as those of southeast Europe where the Turks held sway for very many years, popular music was completely infiltrated by Turkish elements and remains so to this day.

In Turkey itself a number of local popular musical traditions have been developed and transformed through the centuries. Musical ideas were carried from one part of the country to another by the wandering troubadours, ashik, and nomadic gypsy musicians. Both these groups have survived into our own age. The ashiks are poets as well as musicians. They entertain the villagers with the old songs about heroes from Turkish history, love songs and songs about nature, and they usually play one of the many types of lute.

The 21th century

The present century in Turkey has been one of growing European and, more recently, American influence in all sectors of society. Musically, this trend started already in the 1820s, when the Italian musician Giuseppe Donizetti (1788–1856, older brother to the more famous Gaetano Donizetti) was appointed to take charge of the school of music run by the Sultans and Dervishes at the Seraglio in Constantinople. The westernization of music really got underway in the 1920s with the foundation of the Republic and the advent to power of Kemal Atatürk. A European opera was established, European symphony orchestras were started in all the major cities, and encouragement was given to musicians and composers who had received a European training.

A conservatory was founded in Ankara, and the teaching staff there included the German composer Paul Hindemith. All teachers were given an education in European music, and schools completely dropped the teaching of Turkish music. As a result, Turkish children seldom encountered traditional Turkish music at school. Instead, they sang German songs with Turkish words. Since the 1980s, this has successively changed so that today the school children get more into contact with Turkish music.

Traditional Turkish music still survives, however, in many rural areas. In recent years it has been revived by certain professional musicians and by associations of people with an interest in it, e.g. Halk Müzik Derneği, the Folk Music Society. The native musical forms are far from extinct in Turkey, but they are changing rapidly under the influence of Western, North African and Indian popular music distributed by mass media, especially radio and the cinema. Indian musical films are popular in Turkey. The changes thus occurring include the rise of large “folk instrument orchestras” and “folk choirs” playing and singing arrangements of folk tunes and a continuation of the ashik tradition in pop song and variety form, often with female artists replacing the male exponents of traditional music.