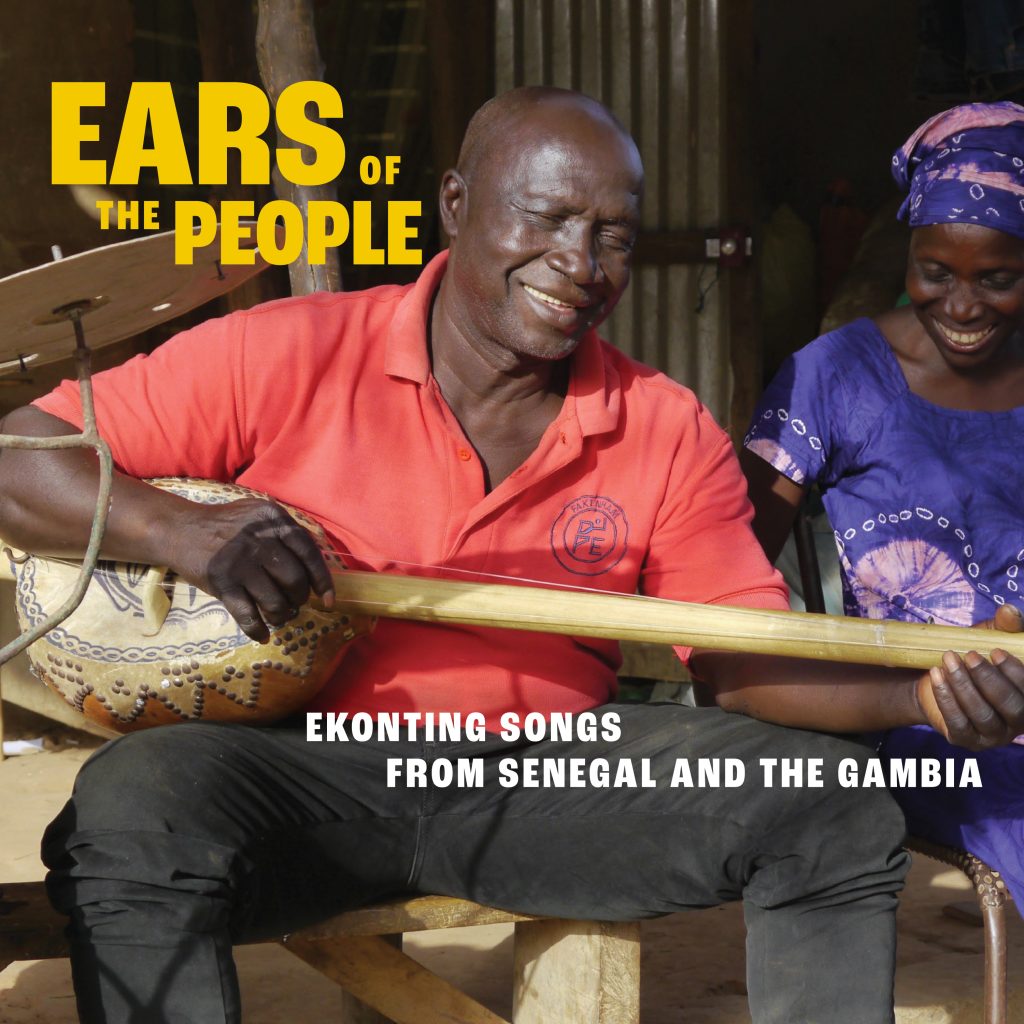

Ears of the People: Ekonting Songs from Senegal and Gambia

The first album of West African ekonting music, Ears of the People: Ekonting Songs from Senegal and Gambia, is a testament to the endurance of music and tradition across the gulf of centuries and some of the most brutal history imaginable. It’s also a showcase for living traditions in West Africa and for the wealth of stories and beauty that a humble, handmade instrument can hold. Though it’s generally acknowledged today that the American banjo came originally from Africa and should be considered an African instrument, for many years, the question remained as to what African instrument exactly was the source of the banjo. Scholars, including Pete Seeger, pointed to instruments like the Wolof xalam or the Mandinka ngoni as possible antecedents. Still, it took the work of pioneering Gambian ethnomusicologist Daniel Laemou-Ahuma Jatta (who also wrote the album’s foreword) to show the Senegalese and Gambian ekonting (also spelt “akonting”) as a particularly likely source. In the evening, after work, Jatta’s father played this three-stringed, gourd instrument popular among the Jola people.

What’s remarkable about this recording is how alive and vital the ekonting’s music is today in Senegal and Gambia. The songs on this album, taken from recordings in Senegal made by ethnomusicologist Scott Linford of nine ekonting players, are full of life. Many songs are inspired by the rivalries and clashes between West African wrestlers, but other songs speak of life and love or the tribulations of violence and conflict. Despite being separated over centuries from its New World progeny, the West African ekonting’s unique strumming position (one finger strikes down on a long string while the thumb follows after on a shorter string) is still today one of the most famous banjo strumming techniques, known as “clawhammer banjo.” Just as the banjo today tells a uniquely American story in our voices, the West African ekonting tells the story of the Jola of Senegal and Gambia today as they live their lives.

Yet with all this history, the Jola of Senegal and Gambia don’t think of the ekonting primarily as an ancestor to an American tradition but instead as a living tradition in its own right. The ekonting is for entertainment, courtship, local wrestling matches, and for telling local stories. It’s a folk instrument made by hand for the people who will enjoy it most. For that reason, it’s been rare to find many recordings of ekonting music. Work in the past decade or so brought the ekonting to light. It connected American musicians to the instrument, including banjo legends Bela Fleck and Rhiannon Giddens, who played with ekonting players in Gambia. Ears of the People: Ekonting Songs from Senegal and Gambia, however, is the first full album of ekonting music for a Western label, and it’s an enlightening examination of the instrument’s role in West Africa.

Recorded in the Casamance borderlands region of southern Senegal, near Gambia and Guinea-Bissau, in 2019 by Linford in village squares, adobe houses, and improvised studios, these nine ekonting players present a cross-section of Senegalese society. Players like 71-year-old Abdoulaye Diallo, equally knowledgeable about both Islam and the Jola indigenous religion, whose songs move between personal and political storytelling. “Every song has a significance,” he says. “There is the song, but then there is the story behind the song.” Jules Diatta leads a band called Sijam Bukan from his house in the village of Mlomp and performs songs that accompany Jola wrestling matches, especially the professionals that let the wrestlers strut their way through the village with a parade of supporters. The virtuosic Adama Sambou has toured Europe and is a prolific composer, writing many songs from his home, while ekonting legend Jeandum Djibalen was one of the first ekonting players to professionalize the instrument, moving it from the rice fields to the concert halls. Elisa Diedhiou is one of the few women to play the ekonting and the first to perform as a professional ekonting player. “People look at me like I’m crazy,” she says. “A woman with an ekonting! But when I go to Mlomp or Oussouye, many people come to see me play, and all the old ladies say, ‘Bravo! Bravo!’”

The songs from these musicians range through a wide diversity of subjects, reflecting the lived experiences of the singers. Songs here reflect on a hard day’s work in the fields, gathering with palm wine. Or they celebrate local wrestlers with lyrics full of vocables and popular shout-outs. Some songs are pleas for friendship and peaceful understanding, and others are about the effects of war and regional violence, including a harrowing account of a roadside bombing. Songs tackle subjects like the premature death of a husband, dream girls, latchkey kids, men’s initiation ceremonies… The topics are as varied as the people themselves, and Linford’s brilliant and extensive liner notes bring these stories to life, including translations of some lyrics.

The last song of the album, “Ayinga Bañiil Dane Dibuke Ban” from Abdoulaye Diallo, ponders the future of the ekonting in metaphorical terms. “It is our responsibility to take care of it,” he sings. For centuries, Africans and African-Americans have treasured this family of instruments, rebuilding them in a new world under the harsh yoke of slavery or writing new songs for them today in the corner of southern Senegal. This is the real testament here that a humble acoustic instrument made from a gourd, three strings, and animal hide can hold the hopes of so many people across so many worlds.